A Scent of Flowers - by James Saunders (1964)First performed at Wimbledon Theatre, 1964Presented by Michael Codron, in association with Richard Pilbrow, with the following cast at the Golders Green Hippodrome on 14 September 1964 and at the Duke of York's Theatre on 30 September 1964 -

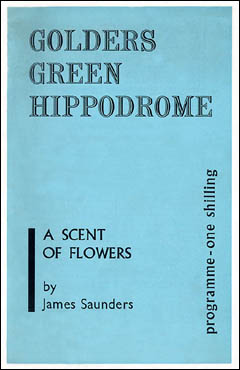

programme - Golders Green Hippodrome, 14 September 1964 photos from the play © 1965 James Saunders published by Andre Deutsch, 1965 ISBN 0 233 95777 4 © 1965 James Saunders published by The Hereford Plays, Heinemann Educational Books (London, England), 1966 ISBN-10: 0435227912 ISBN-13: 978-0435227913 introduction by Elizabeth Haddon © 1965 James Saunders published by Penguin (Harmondsworth, England) 1971 ISBN-10: 0140481125 ISBN-13: 978-0140481129 (Four Plays - James Saunders) also contains Next Time I'll Sing To You + Neighbours + The Borage Pigeon Affair Published by Dramatist's Play Service, 1970 ISBN-10: 0822209950 ISBN-13: 978-0822209959 Mr Saunders unfolds the story of a girl, and why she killed herself. He does it with all the intelligence, wit and sense of theatre of his first West End success, Next Time I'll Sing To You, and with a new tenderness which is very moving. Zoë is a girl any of us might know, a gay, gentle, vulnerable creature ready for love and happiness. She is not the victim of evil intent, but simply of the failures and misunderstandings of ordinary life, and this makes her a deeply poignant figure, both on the stage and within the covers of this book. - (inside cover, Andre Deutsch, 1965) This play is about compassion, about kindness and pity, and it examines, ruthlessly, what we have done with them. Eager for life on our own terms, for emotional non-involvement, for security - that insulated strait-jacket - we have placed a cruel constraint upon the exercise of these virtues. And, in our greed for self-protection, what vanity, what trivial, pitiable vanity we take home to ourselves - "We met once. Briefly, I'm afraid. I'm afraid we didn't get to know each other very well. But I tried. It doesn't matter now. I shall go home with the thought that there was someone I tried to know, and failed; but that it doesn't matter."Is this all we can say of someone we helped to drive to death? Is this all that Agnes can say of the stepdaughter entrusted to her care? If there is anyone so little involved in mankind that he is not roused to passionate repudiation, then he should leave this play unseen, unread. For the rest, if there are any who dare not examine their store of kindness, who dare not know that they did not give of it when it was needed, this play is not for them. They are the strong who can be broken only on the wheel. This play is for the frail, who are broken to pieces by a cry till pity spills like spikenard. Let them imagine, as James Saunders has in this play, a young girl, Zoe, eager, passionate and vulnerable; imagine her hurt by her first real brush with life, perplexed afraid, alone. To whom should she turn? Her family, her friends, her priest? How dare they live if they deny her comfort? Yet a bird with a broken wing is more sure of succour from the human race than is a girl with a wounded heart. It is not that her father, her stepmother and stepbrother lack concern for her. All are, to some degree, concerned, ready with help - but the help is wrong because the motive is wrong. They offer the help they deem necessary, not that which her need demands. "Be kind to me," she pleads with Gogo; but his idea is the new film at the Academy, or a lighthearted scientific investigation of her problem, to "take you out of yourself". None of them realizes that interest, concern, even love, are not the same as compassion and charity (caritas). No one is prepared to share her suffering, to suffer with her, to descend into hell and to be with her during the long climb out of it. Even the Church, upon whose ultimate mercy she throws herself, into whose care she commits herself, interposes between her and the source of all compassion the harsh doctrine of denial. Denial there may have to be, but the medical treatment of a drug-addict is more compassionate than the merciless, kindless thrusting upon Zoe of the whole armour of God. Beneath such weight she is crushed. She cannot even pick it up, much less put it on. And how should she, without a hand to help her, a voice to instruct? Yet without it she is tripped and naked to the cold blast of death. Love in all its forms, it seems, has betrayed and deserted her. Comfort too. Agnes is brisk and practical - "However beautiful and profound and important you think it is, it's no bigger than you are, because it's part of you and you're small, Zoe, like everyone else, small and insignificant. Zoe, you've got to grow up very quickly. You've got to stand outside yourself for the first time in your life and see yourself in retrospect - an emotionally unbalanced child who's got herself into an affair with a married man. Just another. It's happened before. It happened to me. It's unimportant. Nobody gives a damn about it."As if first passion, like first love, were ever small and insignificant! But "nobody gives a damn about it". No one cares. No one who ever knew cares to remember what it was like. In face of Zoe's heartbreaking cry: "Daddy - I'm in trouble..." David is inarticulate. Even Uncle Edgar, kind Uncle Edgar, that "buffon extraordinary", with only a pain where his heart should be, who pushes everywhere in a wheelchair that horrifying memento mori, his aged silent moribund mother, can find no answer but the wrong one, and sadly accuses himself of the final ineptitude - "UNCLE EDGAR: He was... just like everyone else. Go on.What else could one expect from the man who, though he was able to cheer Zoe's childhood with fairy tales, has buried whatever feelings he ever had under a heap of throw-away philosophy summemd up in his speech before the funeral - Well, what shall we take as the text for today? Do you have any fancies, any special requests, our only aim is to please. What about St John of the Sonnets: "Consider not for whom the bell tolls - as long as you can hear it, it must be for somebody else."The gale of laughter which greets this in the theatre is memorable, but longer to be remembered is the silence of cught breath as the realization takes hold: against such brutal buffoonery is Zoe's fragile tragedy played out. Not a laugh, not a jest is wasted in this play. Sid's absurd story about the complications of his personal life - an uneasy threesome who holiday together, and spend evenings playing cards because Sid is in love with a girl whose husband in his turn is "sweet on" Sid - is hilariously funny until one perceives how, in its casual amorality, this relationship marks the gulf between slipshod licence and the anguished desparation of such love as Zoe had experienced. For Zoe the casual, the slipshod, the half-hearted, are impossible. If she gives, she must give wholly. When she discovers that the giving of her love compromises the giving of her faith, the conflict threatens her with disintegration. It is because those to whom she turns for help, guidance, support, are themselves content with compromise, satisfied to be disintegrated and half-hearted, that they can neither understand nor help her. What James Saunders is restating is that, since we are inescapably members one of another, if one member suffers and the others refuse their compassion, refuse to suffer with, then that member is cut off and must, in the temporal sense, perish. Zoe is deserted not by God but by the Church and by us. The emphasis on this aspect of the tragedy is increased as Zoe moved further from "life" and nearer to "death". As the distance between her and "the living" lengthens, so her compassion for them grows and deepens. She understands her father's helpless silence, the silence which had hurt her once so much - "Inside the barriers are broken; there's no logic any more, no cause and effect, just a surging and lappiong of his grief across the broken barriers, splashing against the shell of his breeding, looking for a way out."She understands Gogo's emotional outburst, but is able now to stand clear - "You can't share grief; you're on your own. Go home and cry into your pilllow; your pillow will comfort you.... I envy you your tears; however short-lived they may be."If only there had been one among the living who could have had such understanding in Zoe's grief, to allow her to go apart with it, to respect, to envy, the depth of her feeling. But now it is what we call "too late". It is for Zoe herself, liberated from the inhibitions of the conventions which surrounded her, to show understanding, to grow even beyond compassion. What she extends to Gogo is mercy - and forgiveness that he will so soon forget her. Yet something of him will always be touched by her and by the pain of mortality: "...any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved with mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee." - Elizabeth Haddon (Introduction, Heinemann, 1966) Saunders experiments with his characters as he does with the medium, trying to find out more about the basic components of their existence and their motivations... in A Scent of flowers, Gogo, arguing that heartaches and soul-searchings have no scientific validity, asks whether the force that joins two lovers together is electromagnetic or gravitational. - Ronald Hayman (from the commentary, Neighbours and other plays, Heinemann, 1968) There is usually a single moment to which a serious playwright can look back and say 'That was when the public accepted me'. For James Saunders it may have been the fifteen curtain calls at the West End opening of A Scent of Flowers. - The Observer He communicates 'a loveliness, a glimmering joy, an affection, a yearning after good' in a play which forms 'a unique, an unforgettable experience'. - Harold Hobson (The Sunday Times) |

||||||

James Saunders | bibliography